By Jack Neely,

Knoxville History Project

We may tend to forget that Knoxville, Home of the Vols, Gateway to the Smokies, headquarters of TVA, etc., is also a city with a manufacturing heritage — and one also known for entrepreneurial innovation. Much of its growth — reflected today in many of the old buildings downtown, and the names of streets all over town — was inspired by entrepreneurial innovation.

We may tend to forget that Knoxville, Home of the Vols, Gateway to the Smokies, headquarters of TVA, etc., is also a city with a manufacturing heritage — and one also known for entrepreneurial innovation. Much of its growth — reflected today in many of the old buildings downtown, and the names of streets all over town — was inspired by entrepreneurial innovation.

Someone born in Knoxville in 1850, just before railroads arrived, might live to turn 80 in 1930, in a city that was literally 50 times as big. Almost all of that growth was industrial and entrepreneurial.

It’s hard to say where it started. Maybe in the city’s earliest days, when it was a territorial and later state capital: the legislature met here. What do legislatures need? Liquor, for one thing; Knoxville supported several dozen small distilleries in that era, each presumably offering a slightly different product. But more important was paper, for newspapers and law books for the whole state. With plenty of trees, that was no problem. Knoxville had a cottage printing industry, putting out even sheet music and a few novels, as well as the first books and newspapers ever published in the Cherokee language. Hence, Papermill Road. Its papermill did big business until the 1880s.

Knoxville’s been making interesting things for a long time — and just occasionally, things the world had never seen.

Railroads helped everybody, both passengers and freight, and unlocked several heavy industries, like marble, iron, and lumber—but also spawned its own businesses, as cabinetmakers moved here from other parts of the country to help build the interiors of train cars. Some of them used their fine carpentry skills in other ways, creating coffin factories, for example — or, in one case, violins. Amburn Watson, who had built both passenger cars and coffins in Knoxville, preferred to make musical instruments. He is the city’s best-known violin maker, and the young fiddler Roy Acuff was impressed with his product.

East Tennessee’s abundance of hardwood lumber spawned furniture companies, of course, but even that led to some unexpected results. C.B. Atkin grew up in a furniture family, but chose to specialize in mantels, and did astonishingly well with it. At the height of his career, Atkin claimed to have the world’s largest supplier of wooden mantels.

Sterchi Bros. Furniture

McClung Historical Collection

And Sterchi Brothers Furniture, founded by members of a Swiss family, became one of the South’s great furniture suppliers, but also played a surprising role in the development of the American recording industry. Sterchi’s sold phonographs — they were considered furniture, after all, and in fine polished cabinets even looked like furniture — but around 1920, even as phonographs were getting cheaper, Sterchi noticed the working-class people weren’t buying them. Phonographs had been a luxury item, available mainly to the rich, who favored classical music and opera. Sterchi had an idea that maybe working people might buy phonographs if there were commercial recordings of their own music. In those days, long before Nashville was Music City, the good recording studios were all in New York. So by 1924, Sterchi Brothers Furniture was sponsoring trips to make some of America’s first country-music records — by street performers and banjoist Uncle Dave Macon. The initiative yielded records the people did like.

Architecture was another lumber-related industry. Originally from the Chicago area, architect George Barber moved to Knoxville in the 1880s, and became the city’s best known designer of wooden Victorian houses in the Queen Anne style. Then he tried something unusual for an architect. He created detailed mail-order designs that became popular nationwide. Thousands of Barber houses popped up from Maine to Oregon. The architect never saw most of his houses.

- George F. Barber (1854-1915) Architect

- McClung Historical Collection

Other industries spawned other kinds of innovation. The city’s burgeoning marble industry spawned earth-moving and marble-cutting equipment, much of it created by English-born William Savage. However, Savage came to Knoxville to custom-build some milling equipment for J. Allen Smith — a young flour dealer from Georgia who created several new flours for an international market, among them his best known: White Lily. It became a preferred flour for bakers as far away as Cuba.

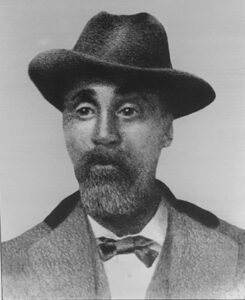

Cal Johnson (1844-1925)

Horse breeder,

jockey, and businessman

(racetracks, saloons, etc.)

One of the city’s most creative entrepreneurs was a man raised in slavery. His name was Cal Johnson, and he was still a teenager at the time of emancipation. According to the legend, he took a government offer of money to disinter corpses from shallow battlefield graves, at about $7 per, for delivery to the National Cemetery here. He did enough of that to buy some property, and eventually start a chain of saloons. Cal Johnson, who loved horses, eventually owned thoroughbreds, and eventually even a racetrack in East Knoxville; its traces remain as Speedway Circle, a neighborhood on a half-mile oval.

Renovated Cal Johnson Building on State Street

Politics closed Knoxville saloons in 1907, and Tennessee banned horse-race betting about the same time, but Johnson was always flexible and open to the next new thing, even in his later years. In 1908, Johnson opened one of Knoxville’s first movie theaters, the small Lincoln Theatre, in a former saloon space on the Central Street Bowery. In 1910, he hosted the first airplane landing in East Tennessee history, at his racetrack. Later still, he was landlord to one of Knoxville’s first automobile dealerships.

As an old man he became a philanthropist, helping found Cal Johnson Park, a city park specifically for African Americans — the site of today’s Cal Johnson Recreation Center.

Sometimes innovators can get a little too creative. William Gibbs McAdoo, a lawyer who was the son of a UT professor, was a young, technologically adept innovator who built East Tennessee’s first electric streetcar in 1890, a line from downtown to Chilhowee Park. Amazing as it was, it broke down a lot and was ultimately unprofitable. McAdoo moved to New York, where he became prominent as a planner of subways, including the first one to go under the East River. But the memory of his failure in Knoxville kept gnawing at him, especially as he heard another businessman had taken the remnants of his streetcar and made a success of it. In 1897 he came back and began building another streetcar to compete with the first one. He hired 200 men to start building it on Depot Street. The main problem was that he had not gotten permission from the city to do so. When police began arresting the workers who were tearing up the streets to lay track, a violent riot erupted. McAdoo, the innovator, was jailed. He later found his true callings, as U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and U.S. Senator from California. Innovative even as an attorney, in 1919 he helped some actor friends found a new kind of talent-driven movie studio called United Artists.

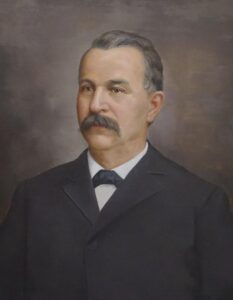

Cowan Rodgers

McClung Historical Collection

Transportation revolutions inspired many young innovators. Cowan Rodgers was a young athlete, more interested in building and repairing bicycles than becoming a lawyer or banker as his affluent family might have expected. He heard about a new invention from Europe, a horseless carriage powered by the internal combustion engine. Rodgers thought he could figure that out on his own. In 1898, he built and test-drove the first automobile ever seen in Knoxville. It was noisy and unpredictable; when he made some improvements on a second car, he had dreams of becoming one of America’s first automobile manufacturers. However, when he heard about the scale of assembly-line car manufacturing contemplated by Henry Ford and others, Rodgers decided he’d be better off as a mere car dealer. Rodgers Cadillac, as it was eventually known, became one of America’s most durable privately owned car dealerships, lasting into the 21st century.

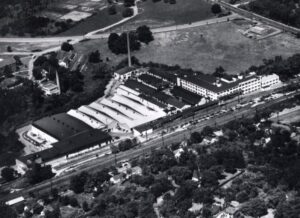

Fulton Sylphon Plant

University of Tennessee Digital Collections

Weston Fulton came here from Alabama, originally to man the U.S. Weather Bureau. He was a weatherman. But he had a daily problem. Every morning, he was expected to measure the level of the then-unpredictable Tennessee River. His office was what they used to call “uptown,” about 65 feet above the river level. Checking the water level involved clambering down the bluff, and then hiking back up. So around 1900, he invented a device that would measure the levels for him, relaying an electrical signal to his office. The device that made it work was a flexible metal bellows he called a “sylphon.” It was never famous by that name, but it turned out to be infinitely useful for hundreds of other inventions, from depth charges in World War I to the top-secret Norden bomb site in World War II — to automobile air conditioners.

Fulton built a big factory on Third Creek, where sylphons — after Fulton’s death in 1946, they were most often just called “bellows” — were manufactured for almost a century. Fulton High School was named for him.

We think of entrepreneurs as middleaged guys, but young people are often the most receptive to new ideas. That was the case, right about a century ago, when there was something new called “radio.” The first person in Knoxville to build a radio was a 15-year-old kid named Powell May. And the first guy to start a radio station, a few years later, was an 18-year-old named Stuart Adcock. He started both WNOX and later WROL — they became arch rivals, but that didn’t bother Adcock much. He had made so much money as a radio pioneer he retired in his 40s and moved to Florida.

Tamale maker, Harry

Royston (ca. 1862-1917)

Knoxville Sentinel / Newspapers.com

Innovators are sometimes just retailers. Harry Royston was a Black man, a former circus carnie, he introduced an invention of sorts that was centuries old, but nonetheless new to Knoxville. It’s believed to have happened in 1887, when he began making and selling tamales on the streets of Knoxville. It was 80 years before Knoxville’s first Mexican restaurant, but tamales became an African American tradition.

After World War I, Ben Bowers saw opportunity in the massive amounts of Army surplus material. He bought much of it up for cheap, and started a retail business on Market Square selling uniforms, tents, and other mostly nonlethal remnants of the Great War. Even today, many people remember Bowers surplus store, or know his Camel Tent company. But they may not remember Bowers’ contribution to aviation. Along with other Army surplus, he bought airplanes, especially “Jenny” trainers. They were Knoxville’s first consumer airplanes, and Bowers — who became one of Knoxville’s first pilots, himself — may be the reason Knoxville had so many local aviators in the 1920s.

The most popular airfield was in Bearden, then a rural backwater. After 1915, when it became part of the national Dixie Highway, it began getting automobile traffic, especially from vacationers in the urban North heading to southern beaches. At first, farmers offered their fields to traveling campers. A few took the next step, and installed public bathrooms, or a little cafe. Then, for those who traveled without tents, some built little cabins for travelers, just to spend the night on the way to Florida; the “motor court” was born. By the 1940s, they had evolved into something new, called motels.

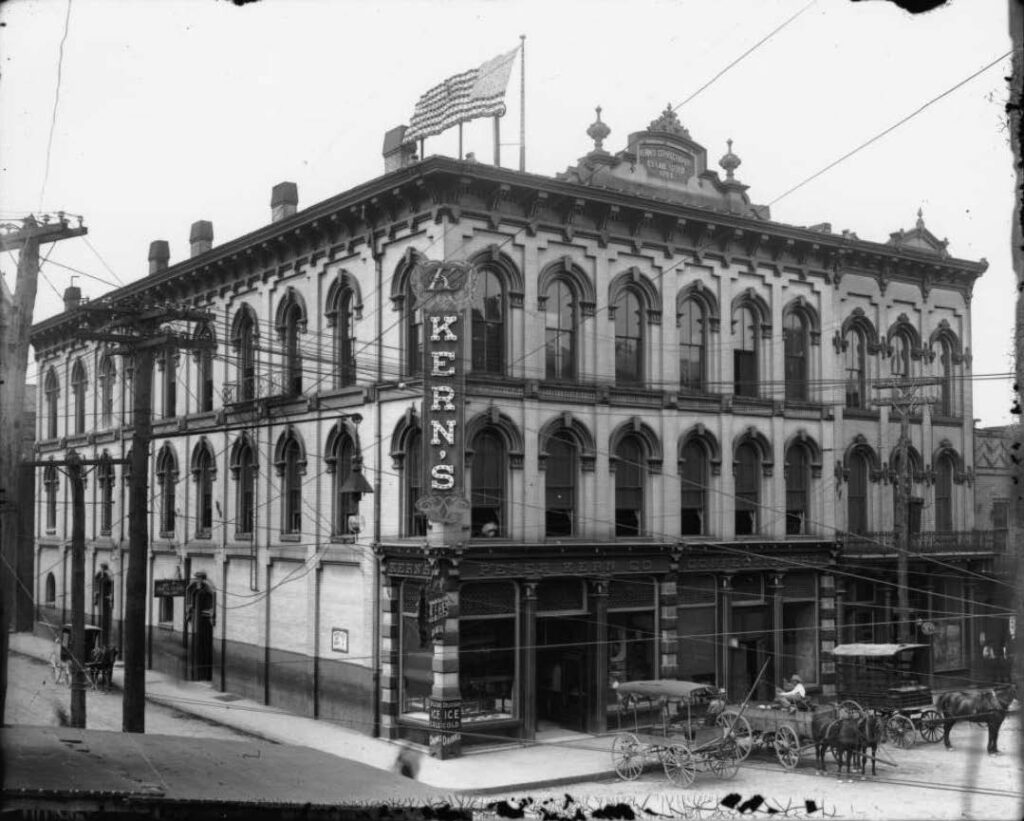

Peter Kern (1835-1907)

Market Square was a constantly evolving experiment in giving the people what they want. German immigrant Peter Kern, a refugee from Europe’s political chaos in the 1840s, had been a cobbler by trade — but when he found himself stuck in Knoxville during the Civil War, befriended another German who suggested they go into business selling molasses cookies to the Union troop trains. The cobbler found he was a good baker, and he kept adding more fun things: toys, candy, fireworks. He opened one of Knoxville’s first soda fountains, with about 40 varieties (including something new from Atlanta called Coca-Cola) and made his own ice cream for a second-floor “ice cream saloon” open until midnight every night. He and his German-born bride also promoted Christmas to East Tennesseans who weren’t yet sure what to make of the Old World holiday, as well as American holidays. Kern was a successful and diversified entrepreneur — and one so popular that he was elected mayor.

McClung Historical Collection

Movie theaters there, run by the Italian Brichetto brothers, advertised their product by amplifying the soundtrack through speakers onto the always-crowded square. (Did you hear that? What does that mean? What’s going on? To find out, you’d have to buy a ticket.)

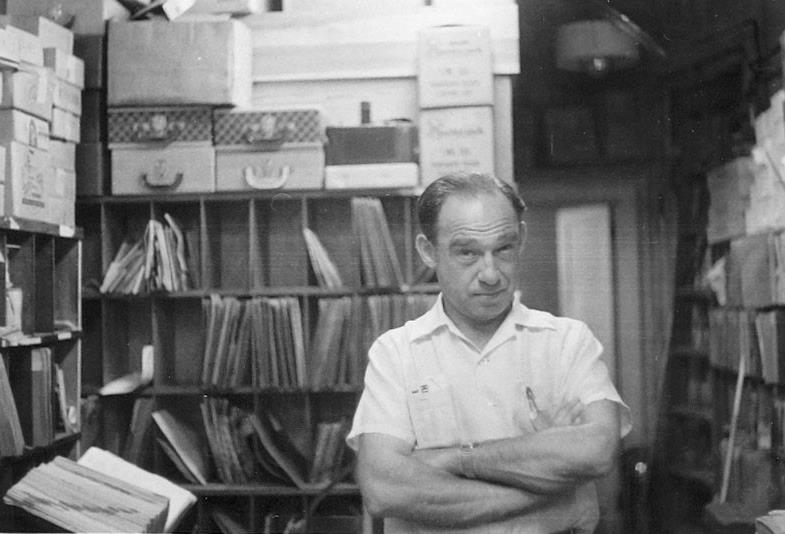

Sam Morrison sold records, and in the same way he’d play the interesting new ones over a speaker onto the street, to get random pedestrians interested in the latest pop music. He sold such an interesting variety of new music to such a wide variety of customers — the people of Market Square, all ages and races — that a scout for RCA came to respect Morrison’s little shop as a sort of bellwether for national tastes.

Sam Morrison, Owner, Bell Sales Record Store on Market Square

Courtesy of Mary Linda Schwarzbart

In the summer of 1954, he had something different, and it turned out to be a phenomenon. It was a freshly pressed 78 from Memphis called “That’s All Right, Mama.” The sound astonished the crowds of Market Square, and he sold the new Sun label record by the hundreds. And it got the attention of RCA. When that record giant first heard of Elvis Presley, all they knew was that his records were selling faster than ice cream cones on Market Square that summer. The following year, they signed him.

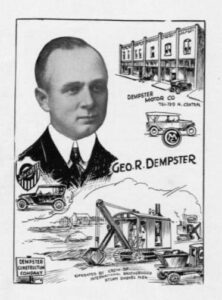

Knoxville’s most famous innovator, though, was a son of Scottish and Irish immigrants named George Dempster. He would be well known in Knoxville history even if he never invented anything. In the 1930s, he was city manager, and did much to establish the Henley Bridge as well as the new McGhee Tyson Airport. In the 1950s, he was city mayor.

- George Dempster (1887-1964)

- From Men of Affairs,1921 McClung Historical Collection

Skipping college, he worked as a young man, often with machinery, and eventually co-founded the Dempster Brothers equipment factory. As one of the thousands who worked on the Panama Canal, he got used to thinking about the most efficient ways of moving thousands of tons of material you didn’t need. While also working as city manager, he came up with a simple idea. In November, 1936, Knoxvillians were surprised to find four big steel bins in the alley between Gay and Market Streets. They had funny slots and hooks on them that nobody could figure out. They did seem like a good place to put garbage, though, and were used almost instantly.

Later, a special truck came by equipped with hooks to carry it off and dump it elsewhere. George Dempster was so proud of them he named them for himself, sort of. These were the world’s first Dumpsters.

Within months, city officials from Louisville, Nashville, and Washington were visiting Knoxville to see this amazing innovation. The garbage problem would never be the same. For many years, Dumpsters were manufactured in the Dempster factory off North Central to meet a global demand.

Knoxville’s been making interesting things for a long time — and just occasionally, things the world had never seen.

Photo by Jennie Andrews

Jack Neely is the Executive Director of the Knoxville History Project, an educational nonprofit whose mission is to research and promote the history of Knoxville. He is a journalist who has been writing about his hometown’s character and heritage for many years. He has written several books about Knoxville and its history, and they can be purchased in various places throughout the city including Union Avenue Books and the Visit Knoxville Gift Shop.