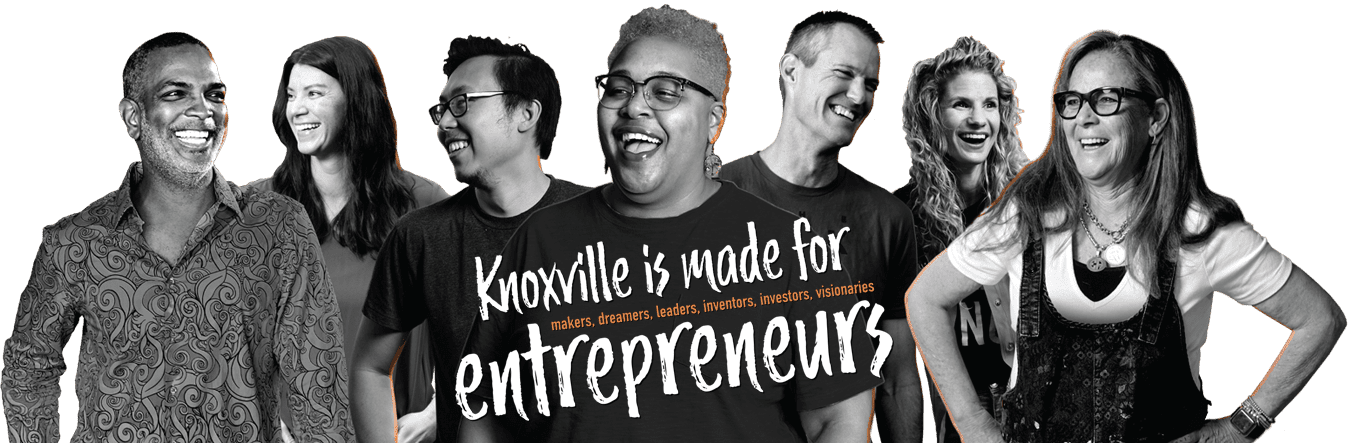

Pictured from left to right at Startup Day 2019: Tom Ballard, PYA; Jim Biggs, KEC; Lynn Youngs, UT Anderson Center; Tom Rogers, UT Research Park; Leah Winter, Winter Innovations; Amy Henry, TVA; Dan Miller, ORNL; Jonathan Sexton, Bandera; Stacey Patterson, University of Tennessee; Maha Krishnamurthy, UT Research Foundation; Grady Vanderhoofven, 3Roots; Derren Burell, Veteran Ventures

By Jim Biggs, Executive Director, Knoxville Entrepreneur Center and Cortney Piper, Innov865 Alliance

It is an exciting time to be part of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Knoxville.

In this city, we’re more than willing to get excited about the latest Vols win or claim Dolly Parton as our region’s patron saint, but we have not always been as proactive about telling the world about what makes our city such a great place to live, work and play.

Our community has been so busy rolling up its sleeves, testing technology in the lab, strategizing in the boardroom and mentoring the next generation of innovators that we have forgotten to let people in on our best-kept secret: Knoxville’s entrepreneurial scene is thriving. We think it’s about time the rest of the country knows that too. From a nationally recognized business accelerator coming to town to concentrated efforts to promote our city’s entrepreneurs, we have some fantastic developments to share.

“Put simply: Knoxville is made for entrepreneurs. We know what we’re doing and want more people and businesses to recognize that too.”

The Knoxville Entrepreneur Center serves as our city’s “front door for entrepreneurs.” Our mission is to build a community where entrepreneurs have access to the capital, customers and talent they need to be successful. We are a member of the Innov865 Alliance, a group of companies and stakeholders dedicated to advocating for Knoxville’s startups and entrepreneurs, ensuring our ecosystem is strong, vibrant and coordinated. The Alliance’s vision is to be a “nationally recognized” hub of innovation and entrepreneurship by leveraging our region’s world-class research, creative and technological capabilities to build the most connected and diverse startup community in Tennessee.

Our work is in line with the City of Knoxville’s latest commitments to bolster its entrepreneurial community. Mayor Indya Kincannon’s proposed 2021-22 city budget emphasizes investments in five priority areas, one of which is “thriving businesses and good jobs.” In this category, the proposed budget would provide over $1 million to support the City’s economic development partners, $90,000 in new funding to support business development in the Latino community, and $150,000 in new funding for KEC, including support for the 100Knoxville project to grow Black-owned businesses.

KEC and the Alliance’s efforts to grow and support our entrepreneurial community also wouldn’t be possible without the brilliant minds and extensive resources of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the Tennessee Valley Authority and the University of Tennessee. These three entities recently came together to support the launch of a Knoxville Techstars accelerator in 2022. Over the next three years, the Techstars accelerator will engage 10 startups a year, attracting new entrepreneurs from around the world to start and grow their businesses right here.

Before launching the accelerator, Techstars released an assessment of Knoxville’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, highlighting both what makes our community so great and areas where we can continue to grow. Techstars identified five primary benefits of our region: large research institutions, excellent quality of life, relatively low cost of living, deep pool of technical talent and exciting support organizations for startups. We couldn’t agree more.

The report also identified six “gaps” where our community can continue to grow. Those gaps include funding, support for growth-stage companies, participation, access, measurement and perception.

Perception, or the fact that many people in our state and city don’t know how well our companies are performing, was number one. Even though we’ve had many successful ventures over the years — Arkis Biosciences, Genera, EDP Biotech, Cirrus Insight, and Gridsmart, to name a few — this report made us realize how we need to do a better job sharing our triumphs within the community and on a larger scale.

We believe Knoxville is a wonderful place to start and grow a business. Our nationally recognized institutions, organizations, and resources are incredible assets for anyone looking to make it as an entrepreneur. Yet, simply having access to TVA or business support from KEC isn’t enough to make Knoxville great. The secret to Knoxville’s thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem is connection. Our organizations, groups, and experts continually collaborate and connect to ensure that we’re offering the best resources, opportunities, and expertise. Unlike larger cities, Knoxville entrepreneurs have ready access to this interconnected network of change-makers and leaders in their respective fields.

Put simply: Knoxville is made for entrepreneurs. We know what we’re doing and want more people and businesses to recognize that too. We have the talent, labs, resources and know-how to transform our community and the world around us. This city is made for makers, dreamers, leaders, inventors, investors and visionaries. Now is our time to highlight the great work innovators in our city are doing every single day, which is why we’re launching the Made for Knoxville campaign.

Made for Knoxville will elevate awareness of Knoxville’s diverse entrepreneurial ecosystem, and inspire action. The goal is to connect and empower the diverse entrepreneurial community in the Knoxville region — ranging from “solo-preneurs,” makers, growth-stage tech companies, investors and established institutions.

Over the next few months , KEC will release dozens of inspiring, incredible stories about the hardworking men and women who make our entrepreneurial scene so vibrant. From hard-tech researchers to artisans, we are letting the world know that Knoxville is truly “made” for entrepreneurs. Come join us.

Chris has spent over 20 years building businesses,

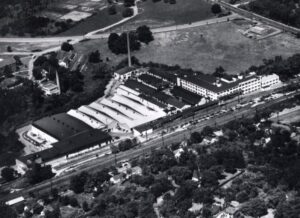

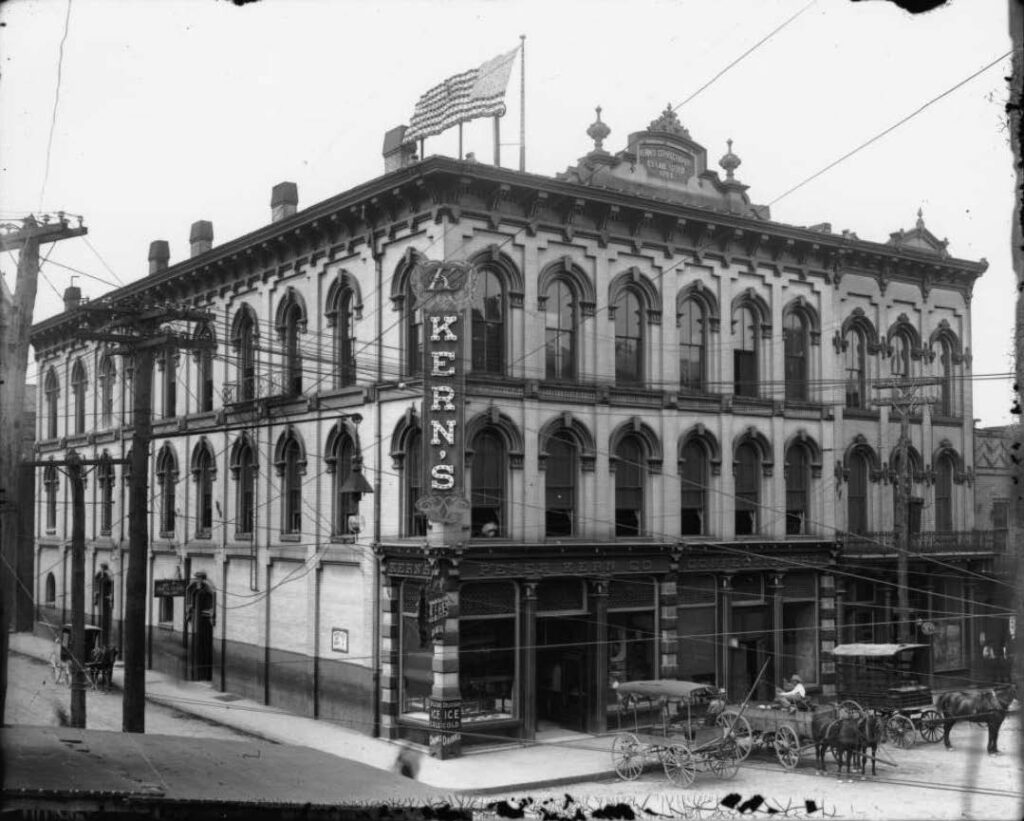

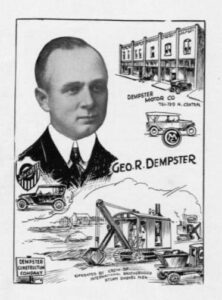

Chris has spent over 20 years building businesses,  We may tend to forget that Knoxville, Home of the Vols, Gateway to the Smokies, headquarters of TVA, etc., is also a city with a manufacturing heritage — and one also known for entrepreneurial innovation. Much of its growth — reflected today in many of the old buildings downtown, and the names of streets all over town — was inspired by entrepreneurial innovation.

We may tend to forget that Knoxville, Home of the Vols, Gateway to the Smokies, headquarters of TVA, etc., is also a city with a manufacturing heritage — and one also known for entrepreneurial innovation. Much of its growth — reflected today in many of the old buildings downtown, and the names of streets all over town — was inspired by entrepreneurial innovation.